BETTY BRODERICK

SYNOPSIS

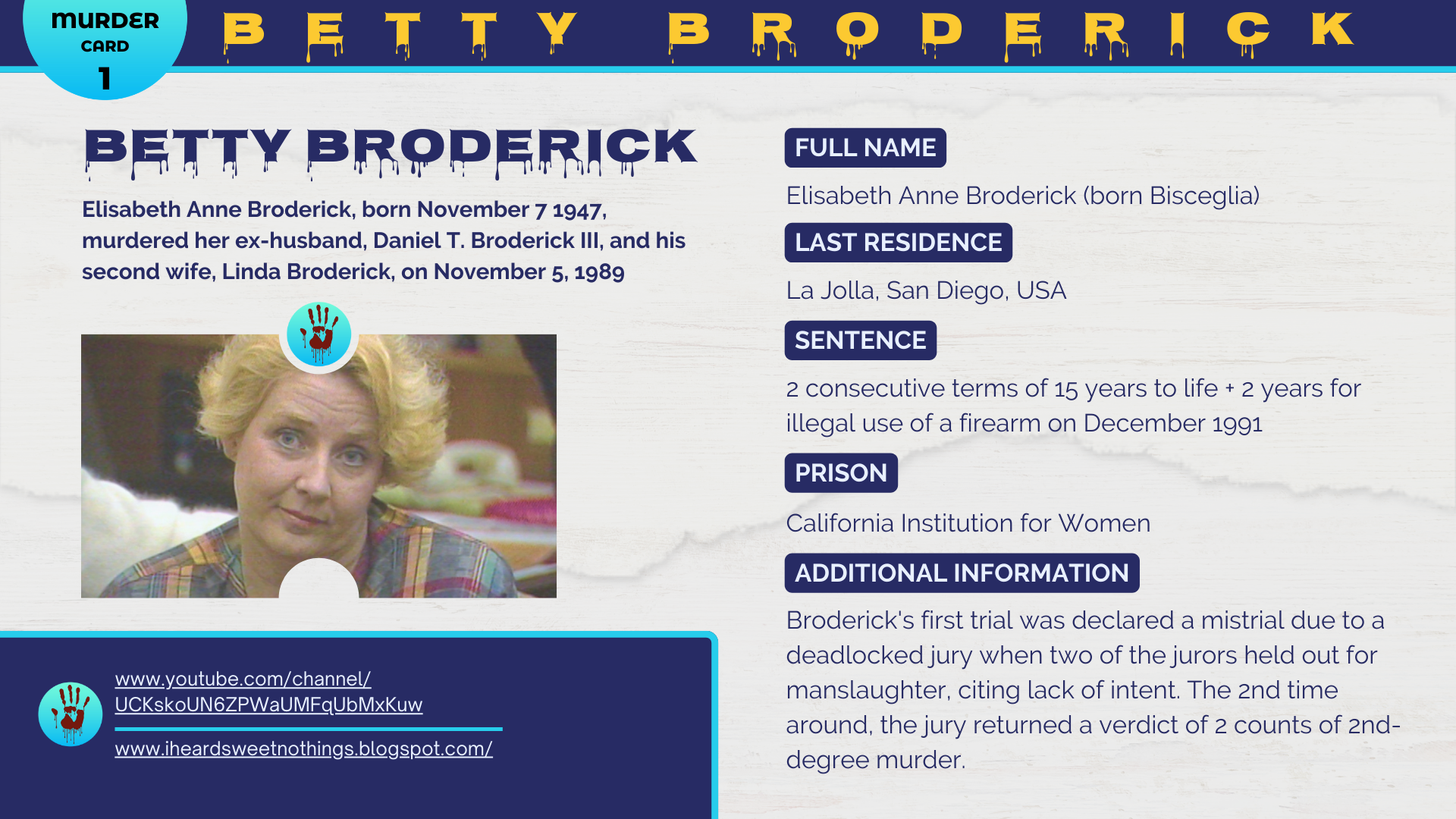

Betty Anne Broderick was convicted of murdering her ex-husband, Daniel T. Broderick III, and his second wife, Linda Broderick, on November 5, 1989. At a second trial that began on December 11, 1991, she was convicted of two counts of second-degree murder and later sentenced to 32-years-to-life in prison. The case received extensive media attention. Several books were written on the Broderick case, a TV movie was televised in two parts In 2020, and just recently, an 8-episode miniseries was produced and aired on Netflix. It was this series that spurred me onto covering this one first.

BACKGROUND

In 1982, Dan Broderick employed 21-year-old Linda Kolkena, a Dutch American and former flight attendant for Delta Air Lines, as his legal assistant. By October 1983, Betty Broderick began to suspect an affair between Dan and Kolkena, which Dan refuted. Despite Betty's objections, Dan vacated their home in February 1985 and promptly initiated divorce proceedings, leading to a contentious five-year battle that earned the Broderick vs. Broderick case the notoriety of being the most tumultuous divorce in San Diego County history. Dan ultimately gained custody of their children, whom Betty had delivered to his doorstep sequentially. Betty later asserted that Dan admitted to having an affair with Kolkena all along.

By then, Dan had risen to prominence as a local attorney and was serving as the president of the San Diego Bar Association. Betty alleged that Dan's influence made it exceedingly difficult for her to secure a lawyer for their divorce, placing her at a significant disadvantage. She also accused Dan of leveraging his legal connections to obtain sole custody of their children, sell the family home contrary to her wishes, and deprive her of a fair portion of his earnings.

The divorce was finalized in 1989, four years after Dan filed for it. Betty's behavior grew increasingly erratic over time. She left countless vulgar messages on Dan's answering machine and disregarded several restraining orders prohibiting her from entering Dan's property. She defaced his new home and even rammed her car into his front door, despite knowing their children were in the house at that moment.

Dan and Kolkena were married on April 22, 1989. Kolkena, worried about Betty's behavior, had even suggested that Dan wear a bulletproof vest to their wedding. Nevertheless, Betty was absent, and the wedding went on without any issues. Following the wedding, Betty alleged that Kolkena mocked her by sending ads for facial cream and weight loss treatments.

Those familiar with Daniel and Betty Broderick, as well as the pain stemming from their drawn-out divorce, often feared that the situation would culminate as Daniel had once foreseen: "It won't end until one of us is gone." "This apparently didn't happen overnight," observed Robert W. Harrison, a defense attorney acquainted with the Brodericks.

Betty Broderick's friends depicted her as a woman scorned. Following a 16-year marriage to Daniel, a prominent figure in San Diego's legal and social circles, she felt abruptly discarded as their marriage disintegrated. Due to her Catholic upbringing, Betty, at 41, feared she would no longer belong to what one friend termed "the prim and proper Junior League type."

Betty found it increasingly frustrating that her ex-husband, leveraging his legal expertise and local influence, managed to gain custody of their four children and secure court orders to seal their divorce records. Despite the divorce case being inaccessible to the public, the acrimony it caused has captured media attention.

The divorce proceedings began in December 1988, four years after the initial filing. During the legal battle, Daniel Broderick secured protective orders to keep Betty from his new family. Reports indicate that Betty disregarded some of these orders, resulting in her being incarcerated for several days and fined substantial amounts.

MURDERS

Eight months after acquiring a revolver, and seven months following Dan and Linda's wedding, Betty Broderick drove to Dan's residence in the Marston Hills neighborhood near Balboa Park, San Diego. Using a key she had obtained from her daughter Lee, Betty entered the home while the couple was asleep and fatally shot them. The incident took place at 5:30 a.m. on November 5, 1989, just two days before Betty's 42nd birthday. Linda was struck by two bullets in the head and chest, resulting in instant death; Dan was hit in the chest, seemingly as he was reaching for the phone. Additionally, one bullet struck the wall, and another hit a nightstand. At the time, Dan was just 17 days away from his 45th birthday, and Linda was 28 years old.

Later that day, authorities located Betty's car in Pacific Beach. Within the vehicle, they discovered an empty .38-caliber, five-shot revolver. Police Lieutenant Gary Learn reported that Linda Broderick was found prone on the bed, clad in her pajamas, while Daniel Broderick, attired in his boxer shorts, was found on the floor. The lieutenant suggested that the blast's force may have propelled his body from the bed. Police verified that Betty frequently entered the home without notice, occasionally to see two of her four children who were in Daniel's custody.

At her trial, evidence showed that Betty Broderick had taken a phone from Dan Broderick's bedroom, preventing him from calling for help. Medical evidence suggested that Dan did not die immediately. Initially, Betty claimed to have spoken to him after shooting him, but she later recanted this statement in court, asserting that she could not remember if he had said anything.

The autopsy of Dan's body uncovered a significant detail: a healthy liver. This discovery contradicted Betty's previous assertions that Dan had a "cruel" nature, exacerbated by chronic alcoholism. Yet, the condition of his liver suggested an alternative narrative.

CONFESSION

After reaching out to her daughter, Lee, and Lee's boyfriend, Betty surrendered to the police, admitting to firing the gun five times. She was detained at the County Jail in Las Colinas. During both trials, Betty maintained that she did not intend to kill Dan and Linda, asserting that her actions were not premeditated, which was the central issue of the trial: whether there was intent or not.

Betty portrayed the killings as a "desperate act of self-defense" against a man who sought to dominate her completely. "I had just spent about $400 on groceries that Saturday," she recounted. "I purchased fresh veal, swordfish, and all sorts of wonderful items. Do you think I had any clue? I had absolutely no inkling that I would do this. I was unaware of what I was doing." However, late on Saturday night, Betty found herself unable to sleep. Consequently, she got dressed, entered her car, and began to drive. "Leaving my house, I was uncertain of my destination," she explained. "Occasionally, I would stop by the 7-Eleven at La Jolla Shores for a half-chocolate, half-coffee, and then stroll on the beach. I considered doing that. But instead, I drove to his house." "It infuriates me when people refer to them as the victims. The true victims were my children and me. Two people are deceased, but in reality, there were five victims," she stated, alluding to herself and her four children.

TRIAL #1

Criminal Defense Attorney Jack Early represented Broderick during the trial, while Kerry Wells served as the prosecutor for the State of California. The presiding judge was Thomas Whelan.

The first trial of Betty Broderick concluded without a verdict due to a hung jury, with two jurors advocating for a manslaughter conviction and ten for murder. The jurors remained silent about the deadlock specifics in court. However, an anonymous juror revealed that the initial vote favored murder at 7 to 5, eventually shifting to 10 to 2 by Monday, but no further progress was made. The central issue causing the impasse was whether Betty Broderick harbored "malice" or a premeditated intent to commit murder.

In her defense testimony, she argued that she lacked the premeditation required for a charge of first-degree murder, as her intention was solely to confront him and then commit suicide.

Jurors had five options in the case:

- First-degree murder (the murder was premeditated or considered beforehand)

- Second-degree murder (lacks deliberation)

- Voluntary manslaughter (a killing was committed after a sudden provocation)

- Involuntary manslaughter, (describes a killing that occurs while doing something else without due caution)

- not guilty on any charges.

After submitting a note indicating that the jury was "unable to reach a unanimous decision," the foreman, 26-year-old Lucinda L. Swann from San Diego, an air pollution inspector for the county, informed Judge Whelan in court that the panel was indecisive on whether the case constituted murder or manslaughter. Judge Whelan directed the jury to resume deliberations; however, after 29 minutes, they returned, still deadlocked, and expressed that additional discussion would probably be futile.

Forensic psychiatrist and criminologist Dr. Park Dietz, representing the prosecution, utilized the analysis of Dr. Melvin Goldzband, a previous consultant on the case. Dietz stated that Broderick exhibited histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders. Similarly, Goldzband had diagnosed Broderick as "severely narcissistic" and "histrionic." Clinical psychologist Katherine DiFrancesca, testifying for the defense, also described Broderick as "histrionic" with "narcissistic features."A mistrial was declared by Judge Thomas J. Whelan.

TRIAL #2

During the second trial, a year after the initial one, San Diego Superior Court Judge Thomas J. Whelan excluded evidence that had been admitted previously, specifically the testimony from Marin County marriage counselor Daniel J. Sonkin about Betty Broderick being emotionally and physically battered by Daniel Broderick. It appears as though the goalposts were moved; when the first trial did not conclude satisfactorily, the rules were seemingly altered to direct the outcome in a desired direction.

Reflecting on the testimony from the first trial, the judge stated before sentencing Betty Broderick last Friday that Sonkin’s testimony failed to confirm any emotional or physical abuse. Betty Broderick remarked that the prosecutor was notably aggressive during the second trial. She claimed that Deputy District Attorney Kerry Wells' forceful prosecution, marked by numerous objections to the defense's evidence, unsettled her attorney, Jack Earley. This was particularly crucial when she testified in her own defense, Broderick noted. "Wells objected every time I began to speak," she said. "There was an extensive list of topics I was barred from mentioning as they were deemed irrelevant. Her constant interruptions caused Jack to lose his focus. He missed several questions when his concentration broke, and if he didn't ask, I couldn't respond." Earley, an attorney from Newport Beach, mentioned that Judge Whelan had excluded a significant amount of material he considered pertinent.

In the opening statements, Wells depicted Broderick as a woman consumed by hatred and a desire for vengeance, resenting not so much her divorce from a notable lawyer, but rather the end of her days as a La Jolla socialite. This account was provided by her children, who had witnessed these events. Their marriage was troubled from the start, marred by frequent threats of divorce. Betty would become enraged when he chose to drink with colleagues over returning home, often locking him out. On occasion, she would wedge his favorite ski in the door, causing it to break upon entry. Her anger led her to hurl objects at him, destroy his prized possessions, and, as her daughter attested, she would claw at his arms with her fingernails. Publicly, she often criticized him.

Broderick's defense attorney, Earley, depicted Daniel Broderick as a man struggling with alcoholism, evidenced by two DUI convictions, and who once drove home intoxicated with his three children in the car while his wife was at home with their newborn baby.

After the verdicts were delivered, Betty Broderick remarked that her focus shifted to the sentencing phase. She believed that the logical decision would have been for Judge Whelan to order her sentences to be served concurrently. Despite the fact that two lives were taken, the events occurred "so closely together" that they constituted "a single instance of aberrant behavior," warranting concurrent sentences, according to Betty Broderick.

"It happened so quickly; the gun never moved," Betty Broderick stated. "The bullet ended up elsewhere because a gun recoils. However, it stayed in place. It wasn't as if I fired in one direction and then another. It never happened like that." Had the sentences been concurrent, resulting in 17 years to life, Betty Broderick could have been eligible for parole within 10 years of her sentencing. Instead, Whelan imposed consecutive sentences—on account of two fatalities—meaning Betty Broderick wouldn't be eligible for parole for at least 18 years.

When questioned at the hearing about why she did not end her life as she had claimed she planned to, Broderick answered, "I didn't have any bullets." It appeared that other details were overshadowed by the drama. Broderick had purchased the gun a month before her husband's remarriage. She had practiced shooting, issued threats, and used her daughter's key to enter a house she was legally barred from under a restraining order, as the testimony revealed.

Broderick had long harbored suspicions of her husband's infidelity, which were confirmed when she unexpectedly visited his office on his birthday, only to discover he had been with his legal assistant for most of the day. Overcome with anger, she tossed his garments into the garden, soaked them in gasoline, and ignited them. She accused Dan Broderick of mistreating her and leveraging his legal influence to overpower her during the dissolution of their marriage.

"The family despises these falsehoods because Dan was as honorable and wonderful as anyone could hope to meet," stated his brother Larry. "Hundreds of people share the same sentiment about him. His sole desire was to distance himself from this woman."

Betty acknowledged that her language was becoming increasingly vulgar. She invented offensive nicknames for Dan and Linda, his new partner, and left them in numerous messages on his answering machine. Consequently, Dan decided to deduct $100 for each profanity she uttered, $250 for every trespass on his property, $500 for each unauthorized entry into his home, and $1,000 each time she took one of the children without his consent. Betty alleges that Dan imposed so many fines within a month that she ended up with an allowance of "negative $1,300." The following month, a judge mandated Dan to pay Betty a monthly sum of $12,500, an amount which was subsequently raised to $16,100.

In court, Betty Broderick's diaries were presented, and tapes from Dan's answering machine were played, one of which featured their son begging his mother to refrain from using derogatory language about his father. Kimberly, the couple's eldest daughter, testified that her mother expressed hatred for the girl's father and regretted the birth of their children. She also claimed he exploited an obscure legal provision to sell her house without her consent.

Mental health experts for the defense argued that Broderick was depressed, while prosecution experts labeled her a narcissist. Broderick's retrial, one of the initial cases broadcast on Court TV, led to her conviction on two counts of second-degree murder. The verdict was a compromise, as the jurors were divided on whether the killings were premeditated. Following the trials, Broderick persistently depicted herself as the victim in numerous media interviews.

Kim Broderick, at 21, the eldest daughter of Daniel and Betty, testified that her mother had exhibited violent behavior for years and frequently spoke of killing her ex-husband and his new wife. Her sister Lee, aged 20, testified that after learning of her drug use, Daniel excluded her from his will.

Brad Wright, Broderick's boyfriend following the divorce, stated that the local media have significantly misrepresented Broderick. "She wasn't a socialite," Wright claimed. "She was merely a housewife with four children attempting to resolve a divorce, as she has conveyed to me. Yet, the media persist in labeling her a socialite.

verdict

Twenty-five months and two trials following the murder, she received convictions for two counts of second-degree murder and two counts of using a firearm during the commission of a felony.

Jury foreman George Lawrence McAlister reported that while some jurors, himself included, were inclined towards a first-degree murder verdict, others favored a manslaughter conviction, leading to a compromise decision. This verdict was heavily influenced by Broderick's own account of the events, which was requested to be read again during deliberations. "Her reactions were not those of a normal, reasonable person," he stated. The central issue became understanding Betty Broderick's worldview. The jury, which started deliberations on Thursday afternoon, requested a review of Broderick's 98-page testimony on Monday.

As the trials progressed, Broderick repeatedly shared a narrative—contradicted by Daniel Broderick's friends and family—of enduring emotional abuse from a manipulative former spouse. This narrative resonated with several jurors, according to foreman McAlister. During deliberations, he mentioned, "we considered the possibility of a hung jury." "We all felt some sympathy for her. We recognized it as an immense tragedy," he expressed to the media following the announcement of the verdict. "However, we observed a significant amount of abnormal behavior."

Judge Whelan sentenced Broderick to two concurrent terms of 15 years to life, with an additional two years for using a firearm, as mandated by state law. He described the case as a "tragedy from start to finish." However, he noted that Broderick demonstrated a "high degree of callousness" by shooting the couple and then removing the phone from Daniel Broderick's reach as he lay dying.

Broderick only looked up once during the two-hour hearing, which was when Deputy District Attorney Kerry Wells referred to her as a "very disturbed woman." Setting aside her stack of papers, Broderick turned to her left, smiled at Wells, and then returned to her papers. Wells, having requested the maximum sentence from Whelan, was visibly satisfied upon hearing the sentence pronounced, whispering a soft "Yeah!" in response.

The parole board will decide if she remains incarcerated beyond that point. Had the sentences been concurrent, a term of 17 years to life, Broderick would have needed to serve approximately two-thirds, or about 10 years, before qualifying for parole. Earley requested that Whelan assign Broderick to the California Institute for Women at Frontera in Riverside County, the state's maximum-security prison, due to its proximity to San Diego. Whelan agreed to recommend this location, although the ultimate decision lies with the prison officials. Broderick will stay at the Las Colinas Jail in Santee until the necessary prison documents are assembled, where she has been detained since her surrender.

appeal

Defense attorney Earley stated that a pivotal element of his appeal is the claim that Daniel Broderick had once sought a hitman to murder his estranged wife. Judge Whelan dismissed attempts to submit evidence regarding these claims. "In 1984 and 1985, he inquired within his office about the price for her assassination," Earley remarked, "the assurances that it wouldn't be traced back to him, and the method of execution. He informed several individuals that the conflict wouldn't conclude until one of them was deceased."

distress suit

A lawsuit brought by Betty Broderick, arising from a conflict with jail deputies that was recorded and subsequently broadcast on television, has been dismissed. San Diego County Superior Court Judge J. Richard Haden ruled out Broderick's lawsuit, which targeted attorney James Cunningham and sheriff's Deputy Michele St. Clair, for lacking merit. Judge Haden also dismissed a comparable lawsuit against the county last week.

Haden stated that Broderick, serving as her own lawyer, could not demonstrate how the release of the videotape led to her experiencing embarrassment and emotional distress. Broderick, aged 45, had filed a lawsuit against both Cunningham and St. Clair, accusing them of releasing the videotape.

The videotape captured Broderick, clad in a sweatshirt and underwear, as she grappled with deputies attempting to remove her from the top bunk at Las Colinas Women's Jail. This incident took place on September 1, 1991, while Broderick was awaiting her second trial.

The tape distributed by Cunningham was a modified version of footage recorded by sheriff's deputies, which was broadcasted on numerous television news programs and tabloid shows. He distributed copies of the tape during a press conference he convened at the downtown County Courthouse on September 18, 1991.

Cunningham represents St. Clair, a 25-year-old who has filed a lawsuit against Broderick for injuries purportedly sustained during a jail altercation. St. Clair is seeking $25,000 in damages for a shoulder strain allegedly incurred in the skirmish with Broderick. According to jail authorities, the fracas started when Broderick kicked a deputy and yanked St. Clair's arm while deputies attempted to extract her from her cell. The deputies' intention was to move her to an isolation cell as a disciplinary measure for seizing a jailer’s keys to unlock her handcuffs.

A spokesperson for the sheriff stated that it was standard procedure to videotape inmates during violent incidents. The officials at Las Colinas Jail provided the video to Cunningham after he subpoenaed it for a worker’s compensation claim filed for St. Clair. Sheriff Jim Roache subsequently criticized Cunningham for releasing the video, labeling it "inappropriate and unprofessional." Additionally, Roache refuted allegations made by Broderick's defense attorney during her second trial, which accused sheriff's officials and prosecutors of conspiring to prevent Broderick from receiving a fair trial.

parole hearings

In 2010, the California parole board rejected Broderick's parole after a five-hour hearing where she persisted in attributing her actions to her husband's affair and their acrimonious divorce. "The voices in my head completely dominated," Broderick explained to the board. "I ended the lives of two wonderful individuals who were cherished by many." However, when asked to elaborate on her actions, Broderick reiterated her trial defense: "Linda attacked me, and the gun discharged." Richard Sachs, a San Diego prosecutor in charge of "lifer hearings," commented, "She showed no remorse and made no attempt [to show it]."

The hearing included emotional testimonies from Broderick, her offspring, and members of the Kolkena family. Broderick's children were split on the decision: two advocated for her release, while two opposed it.

The parole commissioners observed that Broderick displayed no remorse for the murders. "Your heart remains bitter, and you are still filled with anger," stated Board of Prison Terms Commissioner Robert Doyle. "There is no significant progress in your personal development. You are trapped in the same mindset as 20 years ago." At the hearing at the California Institute for Women, statements were heard from 10 members of the Kolkena and Broderick families, as well as from Broderick herself, who delivered an extensive statement. She reiterated her claim from her two trials that she had not intended to kill the couple, although she admitted to having violent thoughts as she approached their home. "I saw only one option: to shoot them or myself," Broderick recounted.

Kathy Lee Broderick expressed her longing for her father but conveyed to the board that her mother could reside with her. "She deserves to spend her later years outside of prison walls," she stated.

Kathy Lee's brother, Daniel Broderick, stated that their mother was fixated on justifying her actions and should remain incarcerated. "She has never expressed remorse or recognized the consequences of her actions," remarked Mike Neil, a close friend of Dan Broderick and a notable San Diego attorney. "Should she be released, I believe she would pose a threat to society and is capable of committing similar crimes," he added.

The last parole request for Broderick was on January 4, 2017. Following a daylong hearing, a two-member panel concluded that Broderick was not suitable for release and denied her parole for the maximum term of 15 years. However, Broderick may be eligible for an earlier hearing if she fulfills specific criteria. Despite expressing remorse at one point, the parole panel virtually closed the possibility of her release from prison.

the public torn

Overnight, Betty Broderick became emblematic of the fury and vengeful desires that are all too common among divorcing couples. At a La Jolla cocktail party following the murders, a man with his younger second wife quipped, “I suppose it’s ‘Be Nice to the Ex-Wife Week.’” However, numerous women identified with Betty—a spouse who resisted being crushed when she was stripped of her family, friends, and lifestyle at her husband's behest. The case polarized the community, with some viewing her as an unrepentant murderer and others as a woman pushed to violence by a bitter divorce and emotional mistreatment from Daniel Broderick, a prominent attorney.

Shortly after her story was published, hundreds of individuals, predominantly women, reached out to Betty and local newspapers. They expressed that although they do not condone murder, they empathize with the rage that led to it. "I believe every word Betty says—because I've lived through it," one woman stated. "Lawyers and judges seem to ignore the need to shield mothers from this kind of sanctioned emotional abuse." Another commented, "The unfairness in court proceedings and financial settlements during divorces is often not acknowledged or understood, except by those women who go through it. Isn't it time we scrutinized our judicial system and the way we handle divorces?"

The divorce became infamous as the most contentious in San Diego's history, drawing national attention. She alleged she was 'a woman scorned,' having been divorced by her affluent lawyer husband three years prior, who, she claimed, had emotionally abused her through unending legal battles. Conversely, the prosecution depicted Betty as a vindictive woman who had harassed Dan and Linda for years, prompting his numerous legal defenses.

Their divorce battle is a stark representation of the tragedies that unfold when one spouse suddenly realizes their happiness has ceased, while the other desperately tries to preserve the marriage, clinging to a fairy tale untouched by reality. It stands as a landmark case, highlighting the harsh truth that in divorce, often the party in control of finances may emerge significantly ahead, while the other may barely retain the clothes on their back. Furthermore, it has brought to the attention of both women's and men's divorce-reform groups the reality that existing divorce laws do not always offer adequate protection in every unique circumstance.

the media

Two days before the death of Daniel T. Broderick III, Betty Broderick was served with legal documents from her ex-husband that felt like "hammers at my head," she recounted in an interview with The Times. She described these papers as the culmination of a series of "overt emotional terrorism" acts by him. When questioned about any sense of relief following the deaths of Daniel and Linda, she expressed uncertainty, saying, "I don't know what I feel. There are times of peace, but then there are days like today when lawyers, psychiatrists, and reporters all probe into my past... I'm unsure if my words will be turned against me. For a moment, I thought it was all over. But now, I find myself reliving everything once more."

She persists in characterizing her actions as self-defense. "All I was trying to do that morning was to make it stop," she asserts. "My lawyers are frustrated because there's no law that acknowledges my right to defend myself against such an assault. He was destroying me—both of them were, covertly."

An article in the Los Angeles Times Magazine about the Broderick case inspired the creation of a TV film titled "A Woman Scorned: The Betty Broderick Story," followed by a sequel, "Her Final Fury: Betty Broderick, The Last Chapter," both released in 1992. Additionally, the murder was portrayed in a "Deadly Women" episode from season 4, entitled "Till Death Do Us Part."

Broderick has given numerous interviews on television and in magazines. She has been featured on The Oprah Winfrey Show twice, as well as on Hard Copy, 20/20, and Headliners and Legends. Her story has inspired at least four books. More recently, her story with Dan Broderick, from their early years to the homicides, was depicted in the second season of the TV series Dirty John, which was broadcast on Netflix.

"The Betty Broderick Story" on Netflix delves into the impacts of abuse and manipulation within relationships, highlighting how persistent patterns of abuse can mold an individual's behavior to a breaking point.

Alexandra Cunningham, creator of the Netflix series, discusses her reasons for selecting The Betty Broderick story: "Many of my friends' parents had divorced. We came from similar socioeconomic backgrounds, and the thought of one of my mother's friends snapping and murdering her ex-husband and his new wife seemed almost like a sensational tabloid story. However, I lacked any personal experience to truly understand that mindset. My own parents hadn't divorced. It felt like something straight out of the New York Post— that level of sensationalism," says Cunningham.

Upon revisiting the case through Bella Stumbo's book "Until the Twelfth of Never," she found she could empathize with Broderick's perspective much more. "I've realized I'm no longer a teenager. As a woman in her 40s with children, having similar opportunities to Betty, I can imagine myself in her position, feeling that sense of panic and desperation—the fear of abandonment, deceit, and solitude, pondering the consequences of discovering years of lies. How would that affect my grasp on reality, trust, and the belief in my own sanity?" she reflects. This epiphany was transformative. "The thought of how to handle my anger, the consequences of unleashing it, and whether it could ever be re-contained also troubles me. The answer is likely negative, which is why the story has gained significant emotional depth over time, compelling me to tackle it now, as I've come to identify with Betty, albeit without the crime."

what now?

At 75, Betty Broderick has spent more time in prison than she did as Mrs. Daniel Broderick. Her unsuccessful parole application has rekindled strong feelings about a case that inspired several books and two TV movies featuring Meredith Baxter from "Family Ties." This was her first opportunity for parole since the 1989 murders. The Brodericks' four children are split on whether she should be released. Larry Broderick, Dan's brother, has dismissed Betty's narrative of victimhood as a web of fabrications. He claimed to CNN that she fabricated tales about her ex-husband and his new wife during her trials in the early '90s. Whether true or not, Betty Broderick's story was so captivating that it gained its own momentum. However, it seems it did not hold up over time as she faced the parole board, where hindsight often casts a more critical and severe light.

Broderick is presently incarcerated at the California Institution for Women. Her next eligibility for parole will be in January 2032, when she will have reached the age of 84.

The Betty Broderick trial took place during an era when continuous TV coverage of high-profile trials was relatively new. It marked the first instance of a San Diego case being broadcast live by CourtTV. The presiding Superior Court Judge at the time, Thomas Whelan, who permitted camera access, has since become a federal judge. Kerry Wells, the prosecutor for both trials, now serves as a Superior Court judge in downtown San Diego. Notably averse to publicity, Judge Wells seldom permits camera presence in her courtroom.

A petition was launched on Change.org in 2020 advocating for Broderick's release. It garnered over 2,000 signatures before closing. The outcome of this petition is unclear. As of December 2023, Broderick will have served the full 32 years of her prison sentence.

Was Betty simply a narcissist who pushed her husband into another woman's arms, or was it her husband's actions that drove her to the edge? It is undisputed that she committed the murders and confessed immediately. Yet, the true motivations behind her actions may remain unknown. Did she speak the truth about being emotionally tormented, or is she a controlling, vindictive narcissist who could not bear her ex-husband being with another woman? Testimonies from her children suggest she was overbearing and often excessively harsh in her punishments.

Many of us have reached a point in our lives where we've felt intense rage but refrained from crossing a line. Murder is indefensible, yet it's hard not to feel that Betty was dealt an unfair hand. There are elements of the trials I disagree with, such as the omission of certain evidence in the second trial—evidence that was deemed relevant in the first. Why did it become irrelevant? The only change was the declaration of a mistrial in the first trial due to a hung jury. The jury system itself is also concerning; it seems that conclusions are sometimes reached by pressuring jurors who wish to take a stand, which doesn't necessarily reflect the truth. Additionally, I take issue with the court's response to Betty's use of profanity. She was angry and felt utterly helpless, which she expressed vocally. However, the court labeled her as emotionally disturbed. Expressing anger doesn't equate to emotional disturbance. It's imperative to stop dismissing women's emotions by labeling them as such, as it is a form of gaslighting that needs to end.